Yves GARY Affichages : 4624

Catégorie : AMERICA

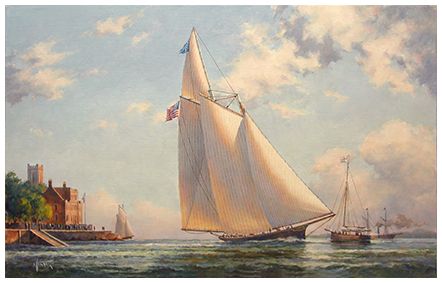

L'America était équipé pour sa traversée de l'Atlantique avec des voiles appartenant au bateau-pilote Mary Taylor. Il portait quarante-cinq tonnes de ballast, ses voiles de course et tout l’équipement étaient rangés dans la cale. Il était bien approvisionné, et, selon les coutumes de l'époque, il transportait un stock d'alcool pour une consommation régulière, et de quoi boire à la santé des vainqueurs et des vaincus après l’arrivée.

L'America était équipé pour sa traversée de l'Atlantique avec des voiles appartenant au bateau-pilote Mary Taylor. Il portait quarante-cinq tonnes de ballast, ses voiles de course et tout l’équipement étaient rangés dans la cale. Il était bien approvisionné, et, selon les coutumes de l'époque, il transportait un stock d'alcool pour une consommation régulière, et de quoi boire à la santé des vainqueurs et des vaincus après l’arrivée.

Le 17 Juin, le certificat de navigation de l'America a été délivré à la douane de New York. Il était rédigé comme suit :

"Registre 290, 17 Juin 1851 William H. Brown, patron, constructeur et propriétaire unique du yacht goélette America. Construit à New York en 1851. Longueur 93 pieds six pouces, largeur 22 pieds six pouces, profondeur 9 pieds, déplacement 170 50-95ths tonnes."

| ** Feu W. T. Porter, rédacteur en chef du Spirit of the Times pendant de nombreuses années et ami du Commodore Stevens, est l'auteur de l'anecdote suivante en relation avec le voyage de l'America pour l'Angleterre: « Avant le départ de l'America, Mr. Stevens avait placé à bord deux douzaines du célèbre vin Bingham, provenant des caves de feu M. Bingham de Philadelphie, père de l'épouse de l'ancien ministre anglais aux États-Unis, lord Ashburton. Il avait plus de cinquante ans d'age et le Commodore pensait le boire à la santé de Sa Majesté. Il semblerait que excellente femme du Commodore, par souci de rangement, a dissimulé ces deux douzaines de Madère dans un recoin secret, de sorte que quand le bateau a été vendu, le vin est resté dans l'America. Mr. Stevens supposait que, malgré une certaine surveillance, le vin avait été débarqué, et n'a découvert son erreur qu'à son retour à la maison. Il a alors immédiatement écrit au Seigneur de Blaquiere alors propriétaire de l'America que s'il voulait regarder dans une certaine cache, il y trouverait un vin « doublant le prix du bateau » mais que bien sûr c’était un cadeau.» |

L'America a été livré à ses propriétaires le lendemain, était prêt à prendre la mer le 20 Juin, et a appareillé le lendemain matin pour le Havre. Il y avait six hommes d’équipage. Le capitaine Dick Brown, un pilote de Sandy Hook, copropriétaire de la Mary Taylor, était maitre d’équipage secondé par Nelson Comstock. MM George Steers, James R. Steers et le jeune Henry Steers, le fils de ce dernier, âgé de 15 ans, étaient passagers mais pouvaient aider pour les manœuvres ou la surveillance. Avec le cuisinier et le serveur, l'équipage du navire comptait treize personne. Le Commodore Stevens, Edwin A. Stevens et George L. Schuyler pensaient rejoindre le yacht en France, mais comme M. Schuyler a eu un empêchement au moment de partir, le colonel Hamilton, son beau-père, est allé à sa place, traversant l'océan en bateau à vapeur comme MM Stevens.

Les incidents de la traversée de l'Atlantique, qui a été effectuée en 17 jours 1/2, sont particulièrement intéressants, car c'était le premier yacht qui traversait l'océan dans les deux sens. Les seuls faits concernant le voyage qui ont été conservés sont contenues dans un journal personnel, ou journal de bord tenu par James R. Steers. Ce livre est entré en possession de James W. Steers, fils de George Steers, de Brooklyn, et est encore dans sa famille.

Ce journal souvent plein d'humour commence avec l'entrée suivante le 21 Juin, 1851:

« Quittons le pied de la 12eme Rue à huit heures. Neuf heures, prenons le vapeur qui nous remorque sur l'East River. Onze heures, à 10 miles au large, nous partons avec nos amis. 13 heures, George Gibbons est venu à bord avec ses agents. 13 heures et 12 minutes, le bateau à vapeur Pacific (un des premiers transatlantiques) nous dépasse et nous donne neuf bans et deux coups de canon que nous lui retournons avec autant de bon cœur. A 15 heures, passons Sandy Hook à 11 nœuds. A 22 heures plutôt barbouillés; capitaine, second et compagnon charpentier prenons un peu de brandy, environ 10 gouttes. »

Ayant ainsi consciencieusement enregistré la mesure de l'indulgence de ses compagnons, M. Steers enregistre les données nautiques avec de fréquentes références à la cuisine du navire.

Le 22 Juin il note: « Mise en place de la voile carrée, ou Big Ben, comme l'appelle le capitaine ». Ce jour-là le navire a parcouru 284 milles, la meilleure distance en 24 heures. Deux jours plus tard, il faisait 276 milles en 24 heures. Sur le journal de ce jour-là on lit: « Commencée avec une brise légère. Croisé un bateau avec une grande croix dans son hunier avant; n'était pas assez près pour parler. Avons pour le dîner un beau morceau de rôti de bœuf avec petits pois, du riz, du pouding pour le dessert. Tout se passe bien à bord et c'est un peu une surprise pour tout le monde ».

Le 22 Juin il note: « Mise en place de la voile carrée, ou Big Ben, comme l'appelle le capitaine ». Ce jour-là le navire a parcouru 284 milles, la meilleure distance en 24 heures. Deux jours plus tard, il faisait 276 milles en 24 heures. Sur le journal de ce jour-là on lit: « Commencée avec une brise légère. Croisé un bateau avec une grande croix dans son hunier avant; n'était pas assez près pour parler. Avons pour le dîner un beau morceau de rôti de bœuf avec petits pois, du riz, du pouding pour le dessert. Tout se passe bien à bord et c'est un peu une surprise pour tout le monde ».

Le 26 Juin, ils avaient « bons vents, rôti de dinde et le brandy », et fait 254 milles. Le lendemain, avec des vents légers, le parcours était de 144 milles. M. Steers écrit de l'America ce jour-là: « C'est le meilleur bateau de mer qui ne soit sorti du Hook. La façon dont nous avons passé tous les navires que nous avons vu est la meilleure preuve ».

Le lendemain, il a écrit: « Le capitaine a dit qu'il navigue comme le vent. Nous avons vu la barque Britannique Clyde of Liverpool juste avant 10 heures, et à 18 heures, elle était hors de vue sur l'arrière.»

Le bilan des deux jours suivants est de 150 et 152 milles respectivement. L'entrée dans le journal contient cette plainte: « Épais, brumeux, avec la pluie, je ne pense pas qu'il n'aie jamais plu autant depuis que Noé flottait sur son arche.»

Mais il semble y avoir une consolation car l'entrée continue: "Avons jambon et œufs frits, corned beef, purée de pommes de terre, gâteau de riz au lait pour le dessert ». Le dîner semble avoir dérangé l'estomac de l'écrivain car cette ligne suit: « Devrais-je survivre jusqu'à la maison, ce sera mon dernier voyage sur la mer ».

La distance pour le lendemain était de 129 milles. M. Steers a écrit: « C'est le premier jour où le soleil a brillé, mais seulement une demi-journée, il va pleuvoir avant la nuit."

La distance pour le lendemain était de 129 milles. M. Steers a écrit: « C'est le premier jour où le soleil a brillé, mais seulement une demi-journée, il va pleuvoir avant la nuit."

Mercredi 2 Juillet: 209 milles. Lu dans le journal: « A quatorze heures, affalons le grand foc et envoyons le petit Il ressemble à une chemise sur un perche. Passé un clipper brick qui suit la même route et le dépassons rapidement ». Ensuite, « notre cuisinier n'est pas un très bon traiteur! » ajoute tristement le chroniqueur. Le fait qu'il y avait une grosse mer de face peut avoir eu une incidence sur l'opinion de l'auteur.

La distance parcourue le 3 juillet était de 219 milles, et le 4 Juillet 179. Pendant les trois jours suivants seulement 147 milles ont été parcourus en raison de vents déroutants. Le 8 Juillet la distance était de 223 milles, et le 9, 272 milles. Cette note apparaît le 8: « Notre liqueur est presque terminée ». Et le jour suivant: "nous avons eu à casser une des caisses marquées « rhum »[stock privé du Commodore Stevens], car George Steers avait mal au ventre, et notre propre était épuisé, mais comme nous n'allions pas mourir de faim au milieu d'un marché nous avons donc pris quatre bouteilles, et je pense que cela va nous faire profit ».

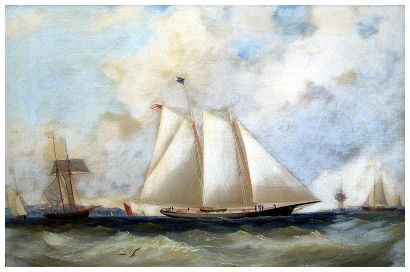

On July 10th the log records: "Fresh breezes and squalls. Three square-rigged ships ahead of us. He [the captain] made them out about 10 a.m., and they have got everything set that they can carry, but we are picking them up fast. The scene is very exciting."

On July 10th the log records: "Fresh breezes and squalls. Three square-rigged ships ahead of us. He [the captain] made them out about 10 a.m., and they have got everything set that they can carry, but we are picking them up fast. The scene is very exciting."

Who with love of the sea in his blood cannot imagine it ? The record for that day was 250 knots, and for July 11th, 166, from midnight to 8 p.m., when Havre was reached.

After the arrival of the vessel at Havre Mr. Steers' journal deals almost exclusively with personal matters, and sightseeing, there being nothing in it of value in the way of data about the vessel.

The Stevens brothers and Col. Hamilton were in France two weeks ahead of the America, and passed most of their time while waiting for the yacht in Paris. Col. Hamilton, in his "Reminiscences," (Scribners, 1869,) throws a most interesting side-light on the sentiment with which Americans then in France looked forward to the America's approaching test against English vessels. He says :

"Such was the want of confidence of our countrymen in our success, that I was earnestly urged by Mr. William C. Rives, the American Minister, and Mr. Sears, of Boston, not to take the vessel over, as we were sure to be defeated. My friend, Mr. H. Greeley, who had been at the Exhibition in London, meeting me in Paris, was most urgent against our going. He went so far as to say :

' The eyes of the world are on you ; you will be beaten, and the country will be abused, as it has been in connection with the Exhibition.'

I replied, ' We are in for it, and must go.' He replied, 'Well, if you do go, and are beaten, you had better not return to your country.'

This awakened me to the deep and extended interest our enterprise had excited, and the responsibility we had assumed. It did not, however, induce us to hesitate. I remembered that our packet-ships had outrun theirs, and why should not this schooner, built upon the best model?"

Col. Hamilton adds: "In Paris we took means to obtain the best wines and all other luxuries to enable us to entertain our guests in the most sumptuous manner."

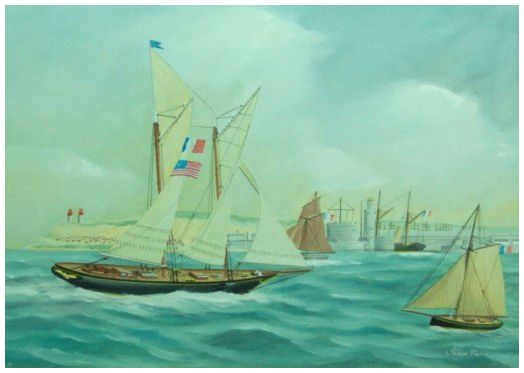

While at Havre the America was fitted out for racing in England. Her hull was here given a smart coat of black, —she wore her prime-coat of gray up to this time, —her racing sails were bent, and she was made ready in every way for the work ahead of her, though she was not put in racing trim until after her arrival in England.

The purpose of fitting out in a French port was to avoid giving Englishmen too much opportunity to study the vessel before she began her racing. This precaution availed little, as events transpired, for a brush with a fast English cutter on the America's first morning in English waters showed what the "glorified pilotboat," as an English writer not inaptly called her, could do. With her first performance in The Solent the history of international yacht-racing gloriously began.

The America, with John C. and Edwin A. Stevens on board, left Havre for England on Thursday July 31st, 1851, and arriving in The Solent that night worked up to about six miles below Cowes, where she anchored, the weather being thick.

The America, with John C. and Edwin A. Stevens on board, left Havre for England on Thursday July 31st, 1851, and arriving in The Solent that night worked up to about six miles below Cowes, where she anchored, the weather being thick.

Commodore Stevens thus described the scene on the America's first morning in English waters, in a speech delivered at a dinner tendered him and his associates at the Astor House, New York, October 2d, 1851 :

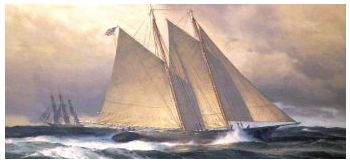

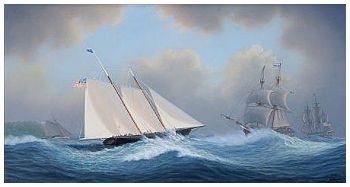

"In the morning the tide was against us, and it was dead calm. At nine o'clock a gentle breeze sprung up, and with it came gliding down the Laverock, one of the newest and fastest cutters of her class.

" The news spread like lightning that the Yankee clipper had arrived, and the Laverock had gone down to show her the way up. The yachts and vessels in the harbor, the wharves, and windows of all the houses bordering on them were filled with spectators, watching with eager eyes the eventful trial. They saw we could not escape, for the Laverock stuck to us, sometimes lying-to and sometimes tacking round us, evidently showing she had no intention of quitting us. We were loaded with extra sails, with beef and pork and bread enough for an East India voyage, and were four or five inches too deep in the water. We got up our sails with heavy hearts ; the wind had increased to a five- or six-knot breeze, and after waiting until we were ashamed to wait longer, we let her [the Laverock] go about two hundred yards, and then started in her wake.

"I have seen and been engaged in many exciting trials at sea and on shore. I made the match with the horse Eclipse against Sir Henry, and had heavy sums both for myself and my friends depending on the result. I saw Eclipse lose tlie first heat and four-fifths of the second without feeling one-hundredth part of the responsibility, and without feeling one-hundredth part of the trepidation. I felt at the thought of being beaten by the Laverock in this eventful trial. During the first five minutes not a sound was heard save, perhaps, the beating of our anxious hearts or the slight ripple of the water upon her [the America's] swordlike stem. The captain was crouched down upon the floor of the cockpit, his seemingly unconscious hand upon the tiller, with his stern, unaltering gaze upon the vessel ahead. The men were motionless as statues, their eager eyes fastened upon the Laverock with a fixedness and intensity that seemed almost supernatural. The pencil of an artist might, perhaps, convey the expression, but no words can describe it. It could not and did not last long. We worked quickly and surely to windward of her wake. The crisis was past ; and some dozen of deep-drawn sighs proved that the agony was over.

"I have seen and been engaged in many exciting trials at sea and on shore. I made the match with the horse Eclipse against Sir Henry, and had heavy sums both for myself and my friends depending on the result. I saw Eclipse lose tlie first heat and four-fifths of the second without feeling one-hundredth part of the responsibility, and without feeling one-hundredth part of the trepidation. I felt at the thought of being beaten by the Laverock in this eventful trial. During the first five minutes not a sound was heard save, perhaps, the beating of our anxious hearts or the slight ripple of the water upon her [the America's] swordlike stem. The captain was crouched down upon the floor of the cockpit, his seemingly unconscious hand upon the tiller, with his stern, unaltering gaze upon the vessel ahead. The men were motionless as statues, their eager eyes fastened upon the Laverock with a fixedness and intensity that seemed almost supernatural. The pencil of an artist might, perhaps, convey the expression, but no words can describe it. It could not and did not last long. We worked quickly and surely to windward of her wake. The crisis was past ; and some dozen of deep-drawn sighs proved that the agony was over.

" We came to an anchor a quarter or perhaps a third of a mile ahead, and twenty minutes after our anchor was down the Earl of Wilton and his family were on board to welcome us, and introduce us to his friends. To himself and family, to the Marquis of Anglesey and his son. Lord Alfred Paget, to Sir Bellingham Graham, and a host of other noblemen and gentlemen, were we indebted for a reception as hospitable and frank as ever was given to prince or peasant."

That the speedy stranger, whose model and rig were new to them, should cause consternation among the English yachtsmen, whose title to yachting leadership had never been questioned, was but natural.

The London Times compared the agitation caused among them by the America, after she had shown Laverock her quality, to that which "the appearance of a sparrowhawk in the horizon creates among a flock of woodpigeons or skylarks."

The Englishmen were free, though not entirely unfriendly, in their criticisms of the America. One writer described her as follows :

"A big-boned skeleton she might be called, but no phantom. Hers are not the tall, delicate, graceful spars with cobweb tracery of cordage scarcely visible against the gray and threatening evening sky, but hardy stocks, prepared for work and up to anything that can be put upon them. Her hull is very low ; her breadth of beam considerable, and the draught of water peculiar, —six feet forward and eleven feet aft. Her ballast is stowed in her sides about her water-lines, and as she is said to be nevertheless deficient in headroom between decks her form below the waterline must be rather curious. She carries no foretopmast, being apparently determined to do all her work with large sheets."

So shy were English yacht owners of the America that Commodore Stevens' challenges for her, posted in the Royal Yacht Squadron's club-house, remained untaken.