Yves GARY Hits: 5234

Category: 1871 : CHALLENGE N°2

A tempestuous passage

A tempestuous passageThe new challenger, Livonia, left Cowes on September 2d and after a slow and tempestuous passage of twenty-nine days, during which she was hove to in a hurricane, and lost sails, broke her foreboom, and carried away her bowsprit, arrived at Staten Island on October 1st. She had proved herself a fine, able sea boat, but the weather conditions did not allow of any show of speed.

She did not create much uneasiness among American yachtsmen, and it was not considered necessary to build a new vessel to beat her. The four boats that were finally chosen by the New York Yacht Club to defend were the two centerboard schooners Palmer and Columbia, both noted as fast, light weather boats, and the keel schooners Dauntless and Sappho, the latter much improved by alterations made by " Bob " Fish after her first unsuccessful season in English waters. She was now considered a very fast boat, especially in a breeze.

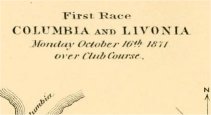

On the day of the first race, October 16th, the wind was light to moderate and the committee of the New York Yacht Club chose Columbia as their representative. The course was the inside one, starting from anchor, and the starting signal was given at 10:40.

On the day of the first race, October 16th, the wind was light to moderate and the committee of the New York Yacht Club chose Columbia as their representative. The course was the inside one, starting from anchor, and the starting signal was given at 10:40.

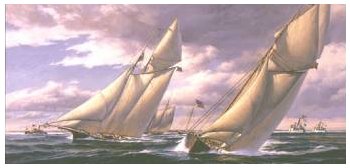

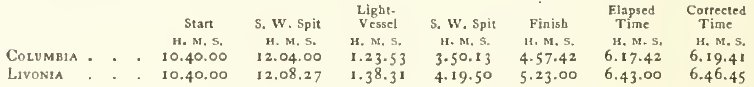

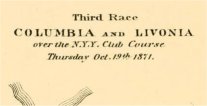

On the crack of the gun mooring cables were slipped, headsails sheeted home and, heeling to the northwest breeze, the two yachts were off, stretching down through the Narrows with sheets well off, and followed by the ever-present fleet of excursion vessels. As a contest the race was uninteresting. The lighter American "skimming dish" as the crew of Livonia styled their adversary, which drew only five feet of water while the English yacht drew 12l4> slipped along so fast in the light breeze that, passing out of the Narrows, only about a mile and a half from the start, she was three minutes ahead. At the outer mark she was nearly fifteen minutes ahead, and at one point of the race she had fully forty minutes' lead on her rival. Toward the finish she was becalmed under the Staten Island bluffs at Fort Wadsworth, and Livonia closed up somewhat; but the Columbia sagged across the finish line 25 minutes and 28 seconds ahead, which, with the addition of the 1 minute 46 seconds allowed her by the Englishman, gave her the race by 27 minutes and 4 seconds, as the following table of the times at the various marks will show:

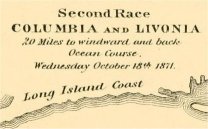

Two days later, on October 18th, the second race was started, the course, according to the terms of agreement, being a windward and leeward one of twenty miles and return, starting at Sandy Hook lightship. Everything would have been well if the course had been laid out as called for, but with a west-northwest wind of fair strength in the early morning, the course, for some reason or other, was laid east-north-east, or fully four points off a true leeward and windward one. By the time the race started it had “piped up" to a cracking, whole sail breeze, which continued to freshen throughout the contest.After considerable discussion in the early morning, before the breeze had stiffened, the American committee again chose Columbia as their representative. When sailing instructions were issued nothing was said in them about which way the outer mark was to be turned. Noting this point, the owner of Columbia went aboard the committee boat for fuller instructions, being told " that it could be left on either hand," a fact of which the Livonia s crew were in ignorance.

Two days later, on October 18th, the second race was started, the course, according to the terms of agreement, being a windward and leeward one of twenty miles and return, starting at Sandy Hook lightship. Everything would have been well if the course had been laid out as called for, but with a west-northwest wind of fair strength in the early morning, the course, for some reason or other, was laid east-north-east, or fully four points off a true leeward and windward one. By the time the race started it had “piped up" to a cracking, whole sail breeze, which continued to freshen throughout the contest.After considerable discussion in the early morning, before the breeze had stiffened, the American committee again chose Columbia as their representative. When sailing instructions were issued nothing was said in them about which way the outer mark was to be turned. Noting this point, the owner of Columbia went aboard the committee boat for fuller instructions, being told " that it could be left on either hand," a fact of which the Livonia s crew were in ignorance.

The Livonia was first off, getting over the line well in advance of Columbia, With a quartering breeze, she hung all her kites aloft and " tore up " the twenty miles of water to the outer mark at a great rate, reaching the stake boat over two minutes ahead of her American rival. Here, owing to the lack of any instructions to the contrary, the skipper of Livonia jibed around so as to leave the mark on the starboard hand, that being the racing rule in England when not otherwise specified. This was a difficult thing to do in the heavy breeze that prevailed. He had a club topsail aloft and was forced to jibe " all standing," as the saying is, and in doing so was set well down to leeward before he could get his sheets flattened down for the close reach back.

The Livonia was first off, getting over the line well in advance of Columbia, With a quartering breeze, she hung all her kites aloft and " tore up " the twenty miles of water to the outer mark at a great rate, reaching the stake boat over two minutes ahead of her American rival. Here, owing to the lack of any instructions to the contrary, the skipper of Livonia jibed around so as to leave the mark on the starboard hand, that being the racing rule in England when not otherwise specified. This was a difficult thing to do in the heavy breeze that prevailed. He had a club topsail aloft and was forced to jibe " all standing," as the saying is, and in doing so was set well down to leeward before he could get his sheets flattened down for the close reach back.

Columbia came down on the mark, and her skipper, knowing that he could turn either way, naturally luffed around it (as the Livonia s skipper would have done had he known), trimming in his sheets as he turned, and cut in between the Livonia and the mark boat, thereby taking the lead.

With the wind four points on the quarter coming down, it was naturally a close reach home instead of a beat, and the leg was in no sense a windward one, not a tack being made by either boat. The wind had hardened to a moderate gale and Columbia s crew were obliged to shorten sail, taking in topsails and furling the foresail. Even then she had all she wanted. Livonia hung on to her topsails and sailed a grand race, but could not catch the flying centerboarder, Columbia crossing the line 5 minutes and 16 seconds ahead, and, when her time allowance was added, winning by 10 minutes 33 seconds.

On finishing, Mr. Ashbury immediately lodged a protest against the Columbia on two counts; first, that by rounding the outer mark as she did she violated the sailing regulations and thereby gained a decided advantage, and second, " in the interest of general match racing, and the danger of violating such regulations by the most obvious unfairness," quoting the exact words of the protest.

This protest was not allowed by the New York Yacht Club committee, which held that in the printed copy of the sailing rules the omission to specify which way the outer mark should be turned left the choice optional. It may be remembered in this connection that almost the same thing happened when the America won the Cup, the Brilliant protesting her for passing the wrong side of a lightship, and the English committee holding that in the lack of definite instructions she had the option of passing on either side. Mr. Ashbury also objected to the course not being a leeward and windward one, as agreed upon, claiming that Livonia would have had the advantage of the centerboard boat in a hard thrash, as she undoubtedly would.

The third race was scheduled for the following day, over the inside course, and Columbia was again chosen as the defending boat. This did not please her crew any too well, as they claimed that they were worn out by the strain of the two previous races, a claim that could have been made with equal justice by Livonia’s crew. There were rumors that they had been celebrating their victory too freely and were not in shape to sail. At any rate, subsequent events should not be charged to, or excused on, these grounds.

The third race was scheduled for the following day, over the inside course, and Columbia was again chosen as the defending boat. This did not please her crew any too well, as they claimed that they were worn out by the strain of the two previous races, a claim that could have been made with equal justice by Livonia’s crew. There were rumors that they had been celebrating their victory too freely and were not in shape to sail. At any rate, subsequent events should not be charged to, or excused on, these grounds.

The race was discreditable from our standpoint from the very start. In the first place, Columbia was late getting to the line, as her crew had not expected her to be chosen again, and it was after twelve o'clock when the race was finally started, the Livonia waiting until the American defender showed up. The wind was southwest, and fresh, not Columbia weather, but Dauntless, which was the  committee's choice, had carried away some of her rigging, and Sappho, the other heavy weather boat, was not on hand.

committee's choice, had carried away some of her rigging, and Sappho, the other heavy weather boat, was not on hand.

Columbia bungled the start, Livonia getting away well in the lead. It is but just to say that the captain of Columbia had been slightly injured in the previous race, and while on board, could not steer the yacht himself. Passing out of the Narrows the Englishman was three minutes ahead, but once clear of the Staten Island hills, Columbia began eating up the distance that separated her from the flying leader and had almost caught her at the Spit buoy, where they turned to go out to the lightship. At this point Columbia s flying jib stay parted, letting the sail stream out to leeward, and she lost some six precious minutes before they could get it in and get her on her course again.

As if this was not enough misfortune for one day, after nearly holding her own to the lightship, which she rounded about a mile astern of Livonia, she broke her steering gear on the way back and became unmanageable, so that the mainsail had to be taken off, and she ran up the bay before the favoring breeze under forward canvas only, crossing the line 19 minutes and 33 seconds behind Livonia, When time allowance was applied this was reduced to 15 minutes and 10 seconds.

The count now stood two to one in favor of America, and the Sappho was chosen to meet the Livonia in the next race, this ending Columbia's connection with the series.

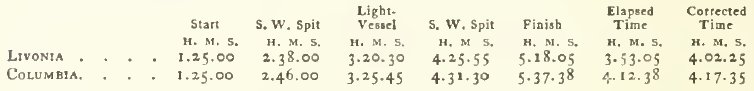

The fourth race was held two days later, October 21st, and was a windward and leeward one of 40 miles, starting from Sandy Hook lightship. The wind was light southerly at the start, and it looked more like Columbia s weather than Sappho's, The course was set at S.S.W., as the committee expected the wind to haul, which it did, making the first leg a perfect windward one.

The fourth race was held two days later, October 21st, and was a windward and leeward one of 40 miles, starting from Sandy Hook lightship. The wind was light southerly at the start, and it looked more like Columbia s weather than Sappho's, The course was set at S.S.W., as the committee expected the wind to haul, which it did, making the first leg a perfect windward one.

The Sappho's skipper got the best of the start, putting his boat over the line 1 minute and 52 seconds ahead of the English yacht, which was sluggish in the light breeze. The yachts tacked toward the weather mark in slow hitches, without either gaining any decided advantage, until about three o'clock, when the breeze hardened and was soon blowing a reefing breeze. Sappho hung on to her topsails until she was pretty well buried, finally taking them in. The sea was making up hard and fast and Sappho gave a grand exhibition of sailing. Buried until her lee rail was well under, she walked out to windward in a way that made Livonia appear to be standing still; in an hour she had obtained a lead of about 28 minutes and was some two miles ahead when she turned the outer mark. She was frequently buried nearly to her hatch coamings, and a small boat that was stowed in the cockpit, to get it out of the way, was washed overboard and lost. With it, it is said, went a brand new rubber suit owned by Commodore Douglas, the yacht's owner, bought that morning and stowed away in the boat in case the weather became "dusty."

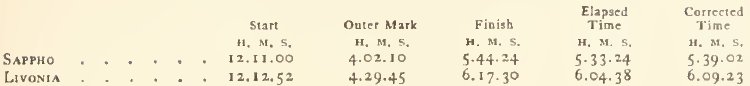

On the run back Sappho was never pushed, though she averaged 12 knots for the entire leg, making the 20 miles in 1 hour 42 minutes and 14 seconds. She crossed the finish line over 33 minutes ahead of her rival, the time of the race being as follows:

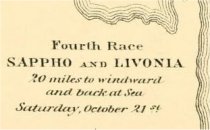

Two days later the last race was sailed over the inside course. It was getting late in the fall for yacht racing, October 23, and fresh breezes were looked for, so Sappho was again chosen, though the Palmer was on hand if the committee wanted to put in a light weather boat as best suited the inside course.

Two days later the last race was sailed over the inside course. It was getting late in the fall for yacht racing, October 23, and fresh breezes were looked for, so Sappho was again chosen, though the Palmer was on hand if the committee wanted to put in a light weather boat as best suited the inside course.

The breeze was fresh at the start, and though Sappho had both working topsails aloft, the Livonia was content with the main, her foretopmast being housed, a common practice of the period when it blew so that a topsail could not be carried.

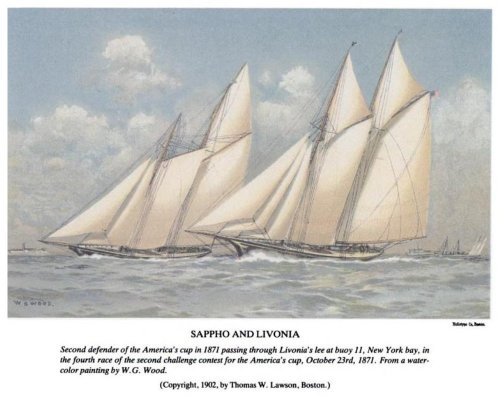

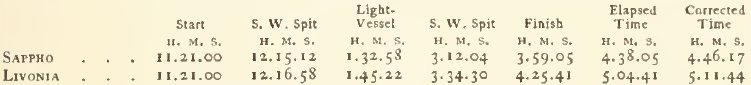

Livonia was first away and worked out a nice little lead of several minutes which the Sappho was some time in overcoming. Going down the lower bay, the American schooner soon “found herself." In the W. by S. wind, making a broad reach of the first leg, she traveled like a torpedo boat, and before the outer mark was reached she had worked through Livonia's lee and taken the lead. On the beat back from the lightship to the Spit buoy she again demonstrated her windward superiority and opened up a lead of 24 minutes. The Livonia could not gain on the run home and was 26 minutes and 36 seconds astern at the finish, as the following table shows:

This race officially ended the series, the American boats having won four races out of the seven, as specified in the agreement.

Mr. Ashbury had other views on the matter, however, and he claimed a continuation of the series on these grounds: That his protest in the second race against Columbia s turning the mark the wrong way should be allowed. (He had already notified the committee that he sailed the third race without prejudice to that protest.) The third race he had already won, making two races, and that the series should be continued; in the event of his winning the sixth and seventh races he would claim and be entitled to the Cup.

In his letter he goes on as follows: “The Livonia will be at her station to-morrow for race No. 6, if the committee decides to entertain my claim. If not, I hereby give you notice that I shall sail twenty miles to windward and back, or to leeward, as the case may be, and as already requested I notify you to send a member of the club on board to see that the rules of the club are complied with. If no competing yacht is at the station, the Livonia will sail over the course, as also on Wednesday, the 25th, at the same time."

In his letter he goes on as follows: “The Livonia will be at her station to-morrow for race No. 6, if the committee decides to entertain my claim. If not, I hereby give you notice that I shall sail twenty miles to windward and back, or to leeward, as the case may be, and as already requested I notify you to send a member of the club on board to see that the rules of the club are complied with. If no competing yacht is at the station, the Livonia will sail over the course, as also on Wednesday, the 25th, at the same time."

This claim was so preposterous that the New York Yacht Club committee did not reply to it, other than to acknowledge its receipt.

The next day a private match between the Livonia and the Dauntless was arranged and sailed off the lightship, twenty miles and return, windward and leeward. Dauntless won, but Mr. Ashbury claimed that as this was a private match and the New York Yacht Club did not send a boat against him, Livonia's going over the course entitled her to the sixth race. Likewise the following day he was at the line ready to start, and no boat appearing to meet him, he claimed that race, though he did not then even go through the formality of going over the course; and so by virtue of four races thus won by Livonia he demanded the Cup. As Captain R. F. Coffin puts it, it was " something like the boarding house keeper's reckoning with the poor sailor: 'Five dollars you had, and five you didn't have, and five I ain't going to give you; an' that makes fifteen.' "

The New York Yacht Club couldn't see it that way, and Mr. Ashbury went home in a rare pet, charging the club with unfair and unsportsmanlike actions, criticising its time allowance rules, etc., and threatening if he ever came after the Cup again to bring his lawyer with him and take the decisions to the courts.

The whole series was very unsatisfactory and stirred up much bad feeling between the two countries. The people of this country were heartily tired of Mr. Ashbury and his letters, and after his departure the New York Yacht Club returned to him three cups he had presented to the club the year before.

Out of the controversy, however, some good had come, for it cleared up a number of disputed points and opened the way to better and fairer racing for the future.