Administrator Hits: 395

Category: ENTERPRISE

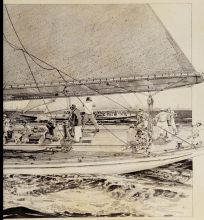

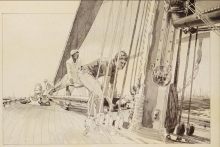

An intricate meshing of gear and teamwork

An intricate meshing of gear and teamworkThe huge J-boats of the 1930s sacrificed simplicity to the demands of speed. To handle the large sails, the crew needed a great variety of special gear. While it was possible to trim small staysails on a simple winch, genoa and quadrilateral jibs were so big they had to be sheeted home by means of multigeared pedestal winches nicknamed coffee grinders because of their large cranks that could be turned by four men at once.

No winch was strong enough to trim the huge mainsail against the force of the wind. Instead, as many as 10 men hooked its sheet to a web of lines and blocks called a grab tackle, which multiplied their brute strength up to 30 times. Spinnakers were gigantic and needed endless adjustments to keep them full (Ranger, the famed J-boat on which these drawings were based, had an 18.000-square-foot parachute spinnaker that was the largest sail ever made).

No winch was strong enough to trim the huge mainsail against the force of the wind. Instead, as many as 10 men hooked its sheet to a web of lines and blocks called a grab tackle, which multiplied their brute strength up to 30 times. Spinnakers were gigantic and needed endless adjustments to keep them full (Ranger, the famed J-boat on which these drawings were based, had an 18.000-square-foot parachute spinnaker that was the largest sail ever made).

Aside from the special gear needed for the heavy work, a J-boat also carried many pieces of equipment that increased the precision with which the vessel could be sailed. The main boom, for instance, was fitted with an elaborate series of winches, blocks and wires so it could actually be bent nearly a foot to impart an aerodynamic curve to the foot of the sail. To ensure that the start of a race could be timed accurately, the afterguard-the skipper and his assistants who directed the paid crew-carried as many as six stop watches, all of which were meticulously synchronized. To guard against equipment failure, all crucial instruments such as compasses

Aside from the special gear needed for the heavy work, a J-boat also carried many pieces of equipment that increased the precision with which the vessel could be sailed. The main boom, for instance, was fitted with an elaborate series of winches, blocks and wires so it could actually be bent nearly a foot to impart an aerodynamic curve to the foot of the sail. To ensure that the start of a race could be timed accurately, the afterguard-the skipper and his assistants who directed the paid crew-carried as many as six stop watches, all of which were meticulously synchronized. To guard against equipment failure, all crucial instruments such as compasses  and speedometers were duplicated.

and speedometers were duplicated.

Maintaining all this gear and using it efficiently made the work of the afterguard and crew immensely complicated. Every one of the 30 or so men in the complement was rigor ously schooled in the precise moves he had to make when the skipper ordered a jibe, tack, sail change or any of the other myriad maneuvers that had to be accomplished quickly and without flaw during a race.

Errors did occur, of course and they were never ignored. "Emphasis was laid on mistakes, with a view to avoiding them in the future," said one J-boat owner. and successful skippers lost no opportunity to improve the expertise of their men. Advised one: "Drill, practice and drill. and practice again. Sail for as long as possible every day until you long for an excuse for a lay day."

Errors did occur, of course and they were never ignored. "Emphasis was laid on mistakes, with a view to avoiding them in the future," said one J-boat owner. and successful skippers lost no opportunity to improve the expertise of their men. Advised one: "Drill, practice and drill. and practice again. Sail for as long as possible every day until you long for an excuse for a lay day."

Success depended on impeccable teamwork; each man had to mesh his efforts with those of his shipmates so that the whole operation proceeded with split-second timing. whether a job called for three crewmen to trim a staysail or for the entire team to man the winches and sheets to bring the boat about. And the fact that these drawings of a crew at work in an America's Cup race reflect orderly concentration rather than furious strain or individual heroics is a testament to just how practiced a great racing team could be.

|

From The racing yachtsby Whipple, A. B. C. (Addison Beecher Colvin), 1918-2013 Drawings by Richard Schlecht |

|