Yves GARY Hits: 4175

Category: 1899 : CHALLENGE N°10

SHAMROCK DISABLED LOSES SECOND RACE

SHAMROCK DISABLED LOSES SECOND RACE Oct. 18, 1899 - The second of the races for the America's Cup was won yesterday by the Columbia owing to an accident to Shamrock. The course was over an equilateral triangle of ten miles to each side, ...

Oct. 18, 1899 - The second of the races for the America's Cup was won yesterday by the Columbia owing to an accident to Shamrock. The course was over an equilateral triangle of ten miles to each side, ...

... and it was so set that the first leg was to windward. The two yachts made a beautiful start and went off on a long port tack soon after going over the line.

When the patrol fleet arrived off the old red lightship there was- quite a formidable roll on the bosom of old ocean, and the sky was a mass of gray clouds, through which an occasional glimpse of cold steely blue shone. At 10:20 three strings of gray bunting were sent fluttering aloft, to the spring stay of the Luckenback, and the mark boat started to log the ten miles dead to windward.

When the patrol fleet arrived off the old red lightship there was- quite a formidable roll on the bosom of old ocean, and the sky was a mass of gray clouds, through which an occasional glimpse of cold steely blue shone. At 10:20 three strings of gray bunting were sent fluttering aloft, to the spring stay of the Luckenback, and the mark boat started to log the ten miles dead to windward.

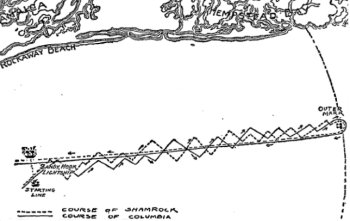

A hundred pairs of glasses were leveled at the flying codeflags on the committee boat and club books were scanned to read the courses. They were “D. C. G.” “D. F.M.," and “D. G. S.," which meant that the first leg of the triangle, was to be east by south, to windward; the second was south-west, one-half south, and the third leg north-northwest to the finish line. At 10:45 the preparatory signal sounded and a puff of blue smoke arose from the rail of the committee boat. At the same instant the blue peter and a red ball were sent aloft and the two racers began to maneuver for position.

Columbia was to windward of the lightship, with her boom well off to port, while Shamrock was hove to with her jib to windward, near the leeward end of the line, as the gun was fired. Columbia luffed up on the starboard tack, and easing sheets went off, free, heading to the northeast, and rounded the committee boat, Shamrock still lying to leeward of the lightship.

Columbia was to windward of the lightship, with her boom well off to port, while Shamrock was hove to with her jib to windward, near the leeward end of the line, as the gun was fired. Columbia luffed up on the starboard tack, and easing sheets went off, free, heading to the northeast, and rounded the committee boat, Shamrock still lying to leeward of the lightship.

Both then filled away, Columbia on the starboard and Shamrock on the port tack and heading for the lightship. They were rapidly approaching each other, when Columbia was put about and, with sheets eased away, headed for the Jersey Beach. Shamrock then luffed close to the line, and was held up in the wind for a few minutes, her sails shaking and her hull rising and falling with a great deal of fuss and splutter as she rode on the steep sea.

The Columbia had in the meantime tacked on the lee bow of the Irish boat, and, luffing out, assumed a position on the weather bow of the green flier,  which at once bore away under the Columbia's stern. Capt. Barr then filled away on the port tack, while Hogarth used sheets again and ran back toward the line. Barr rolled the wheel hard aport, Columbia wore ship and kept on Shamrock’s weather quarter, and Hogarth then luffed a little until the emerald hull was directly in line with the bowsprit of the Columbia, when both headed back toward the line, where Shamrock jibed just as the reports of the warning gun floated out across the sea.

which at once bore away under the Columbia's stern. Capt. Barr then filled away on the port tack, while Hogarth used sheets again and ran back toward the line. Barr rolled the wheel hard aport, Columbia wore ship and kept on Shamrock’s weather quarter, and Hogarth then luffed a little until the emerald hull was directly in line with the bowsprit of the Columbia, when both headed back toward the line, where Shamrock jibed just as the reports of the warning gun floated out across the sea.

She then headed toward the committee boat on the starboard tack followed by Columbia, and paid off right on the line, bringing the American boat broad on her weather beam. The green boat was then, luffed out handsome y upon Columbia’s stern, and headed direct for the line, heeling at an angle that kept the water lapping up to her lee shrouds and flinging an ocean of spray inboard. She was close on the weather quarter of the white boat, and both luffed around the lightship.

The time for the starting was close at hand, and Barr began to worry a trifle, with the lofty sails of the cup hunter towering skyward on his weather beam. He rolled his wheel up sharply, and were out from the lee of his opponent on the starboard tack.

The time for the starting was close at hand, and Barr began to worry a trifle, with the lofty sails of the cup hunter towering skyward on his weather beam. He rolled his wheel up sharply, and were out from the lee of his opponent on the starboard tack.

Shamrock luffed sharply, and, coming up on the port tack, swung about again to starboard between Columbia and the lightship. Just as the latter broke out her baby jibtopsail and headed for the line just thirty seconds before the gun.

Columbia luffed close around the lightship, but the Irish craft held her advantage, and with one sweep of the long tiller Hogarth retained the inside berth. Shamrock swung around beautifully, and was first over the line at 11:00:15, her port rail awash and her towering sails almost completely blanketing the mountains of canvas of the Columbia, which was racing along under her lee quarter. Columbia's time at the start was 11:00:17.

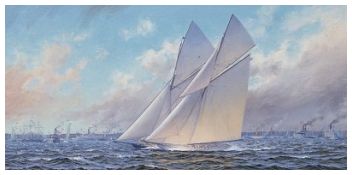

The start was a grand one, and the two giant rocs, their lofty pinions leaning gently to the breeze, made a never to be forgotten marine pageant.

Immediately after crossing the line, Columbia ran up under Shamrock's lee and made an attempt to go through it. Her work at this point clearly demonstrated her superiority to the British yacht in beating to windward. She outpointed Shamrock by fully a quarter of a point, and in spite of this went faster than the challenger. If Shamrock had not been in the way the American yacht could have gone to windward of her course.

Immediately after crossing the line, Columbia ran up under Shamrock's lee and made an attempt to go through it. Her work at this point clearly demonstrated her superiority to the British yacht in beating to windward. She outpointed Shamrock by fully a quarter of a point, and in spite of this went faster than the challenger. If Shamrock had not been in the way the American yacht could have gone to windward of her course.

In just two minutes after the starting gunColumbia had outfooted Shamrock so that she was no longer under the blanket of her enemy's canvas. Those to leeward of the racers saw the shadow of Shamrock’s mainsail creep further and further aft, till at 11:03 the sun shone unimpeded through the creamy yellow of the defender’s chief sail.

Then Shamrock getting the back draught out of this canvas, was forced to go on the port tack in order to escape it, and as she did so, it was clear that she was a beaten yacht. Columbia at once followed her rival to the port tack.

The American yacht was now on the weather bow of Shamrock. On the port tack they had the sea on the weather bow, and were bucking into it with all their power. But at this game the American yacht was much the more comfortable.

The American yacht was now on the weather bow of Shamrock. On the port tack they had the sea on the weather bow, and were bucking into it with all their power. But at this game the American yacht was much the more comfortable.

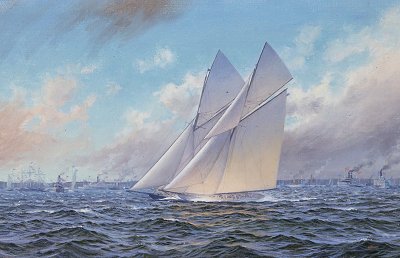

Shamrock’s head plunges were heavy and spasmodic, and at every thump into the round hollows of the sea she flung a shimmering cloud of white spray upon her deck and along the foot of her fore staysail. Columbia, on the other hand, took the seas easily, riding like a duck, and seldom coming down into the hollows with a heavy movement.

The story of the first board to windward is easily told. The British challenger, in spite of the fact that she did not carry any little jib topsail, slowly but surely sagged off to leeward. Columbia, on the other hand, continued to hold on the wind with those eagle claws which are attached to her keel, and while she held on, she kept right on speeding her way off the southward and eastward at a comfortable pace of about seven knots an hour. Her sails were well filled and she appeared in the language of the town, to be “all right."

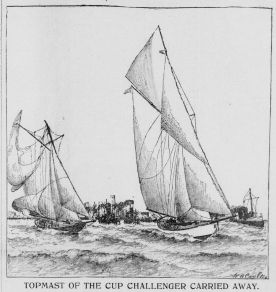

ACCIDENT TO SHAMROCK

ACCIDENT TO SHAMROCKAt 11:15 Shamrock’s skipper began to squeeze her a little to prevent her falling too far to leeward, but in a few minutes he abandoned these tactics. Capt. Hogarth seemed now to have settled down to a conviction that Columbia was too clever for him at windward work, and he sailed his yacht plainly, trying to lose as little as possible on the windward leg, and trusting to Providence to help him make up the difference on the two reaching legs.

At 11:25 the Shamrock’s topmast, with the tremendous strain of the big club-topsail on it, broke on it, broke off close above the cap. The clubtopsail, with its long spars, tumbled over to leeward, and Shamrock was transformed into what sailors call a lame duck. She at once took in her forestaysail, and wore around to run for the Horseshoe, and was later towed to Erie Basin for repairs.

The direct cause of the accident was the parting of the port topmast shroud in the“nip”- that is the portion of this steel wire rope resting in the spreader which extends outboard from the hounds of the lower mast. The strands of wire easily chafe and rust at that point, especially when the shroud is slacked by reason of being to leeward. This support removed, her Oregon pine topmast, 60 feet long and 14 inches in diameter, snapped off like a match.

Columbia, on observing the accident, went on the starboard tack and took in her baby jibtopsail, to ease her topmast and make the windward beat in comfort. The story of her work to the first mark is quickly told. She tacked only twice, going on the port tack at 12:05:20 and on the starboard again at 12:25. On this tack she reached the mark, and eased away around it at 12:39:28.

Columbia then set a reaching jibtopsail, and, heading southwest one-half south, reached away toward the second mark like a racehorse, every sail drawing to its utmost limit and a thin wisp of froth under her lee bow that swept out under her long quarter and was lost in the windy distance.

The Columbia went along in gallant style to the second mark, around which she jibed at 1:33:27, leaving it on the starboard hand. The reaching jibtopsail was sent down on deck in a jiffy, the big balloon jib topsail was broken out and sheeted home two minutes after she had rounded. In came her jib and staysail, and with sheets well off and the wind on her starboard quarter she started alone in her glory for the finish line.

When about two miles away from the lightship the wind shifted a trifle north of east, and the big balloon sail came fluttering down to the deck, the smaller headsails having been set under it. A baby jib topsail was soon sent up in stops, and with everything drawing beautifully and standing up finely to the softening breeze she swept majestically over the line at 2:37:17, again winner, amid a prolonged salvo of hoarse screams from the brazen throats of the flotilla of vessels that crowded about the finish line and the inspiring strains of “The Star Spangled Banner” that floated across the heaving sea from the side wheeler Shinecock.  Columbia's sails were then come lowered and she was towed into the Horseshoe and all on board made snug for the night.

Columbia's sails were then come lowered and she was towed into the Horseshoe and all on board made snug for the night.

On the Regatta Committee boat there was nothing but a feeling of deepest regret at the accident to the Shamrock. What promised to be a rare day of yacht racing was suddenly turned into a day of spoiled sport.

Immediately after the Columbia crossed the finish line the Regatta Committee proceeded to the Horseshoe to confer with the Shamrock people in regard to the third race. They did not find the British racer at the Hook, but they found her managers, who told them that the Shamrock would be unable to race. They wished time to repair and, if possible, to be dry-docked and remeasured. The time was readily granted by the committee and the signal at once set on the committee boat, “No race to-morrow."

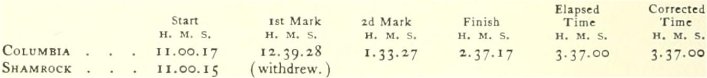

The official summary of the race was as follows :

Columbia made the first leg in 1 h. 39 m. and 11s.; the second leg in 53 m. 59 s. ; the third leg in 1 h. 3 m. and 44 s., and the course in 3 h. 37 m.

Publié le 18 0ctobre 1899 |

SHAMROCK DISABLED LOSES SECOND RACE. |

||

Publié le 18 0ctobre 1899 |

SHAMROCK CRIPPLED AND COLUMBIA HAS A “WALKOVER”. |

Page |

Page |

Publié le 18 Octobre 1899 |

SHAMROCK DISABLED. |

Page |

Page |

No one wanted such an empty victory, but under the terms of agreement covering the point there was nothing to do but accept the race.

The accident showed Shamrock to be too lightly sparred and rigged. Another topmast was put on end the same day, and rigging it was completed the next day. Hoping that she would do better with more ballast. Sir Thomas caused a considerable quantity of lead to be put on board, and on the 18th she was given a remeasurement at Erie Basin. Her water-line was increased from 87.69 to 88.98 feet, and instead of being allowed six seconds by Columbia she was obliged to give a time allowance of sixteen seconds.

The yachts met again the next day, October 19th, but in another inconclusive test, there not being enough wind to finish the race. There was a good northwest breeze at the start, of about ten knots, but it softened within an hour, and fell steadily to a very light air. The course was fifteen miles to leeward, and the boats were three hours and a half making the run to the outer mark. Columbia rounded the mark about an eighth of a mile in the lead. The race was called off at 4.20, when Columbia, leading, was about five miles from the home mark, and a mile and a quarter ahead. The wind was then very light from the westward.