Yves GARY Hits: 4293

Category: 1876 : CHALLENGE N°3

THE GREAT YACHT RACE.

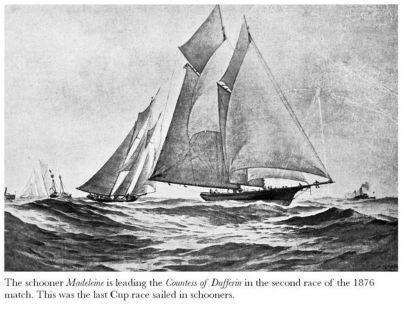

THE GREAT YACHT RACE.The sun., August 13, 1876 - This first race settled pretty conclusively the merits of the two boats and the second race, the following day, was chiefly interesting by reason of the presence of a third boat on the course, though, naturally, not in the contest.

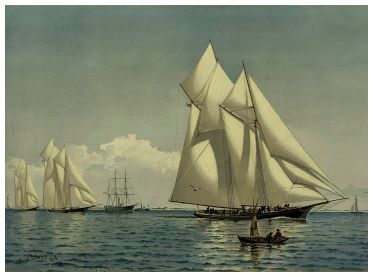

This was the old America, which, in racing trim and with a full racing crew aboard, went over the line after the last boat had started and sailed over the course with the contestants.

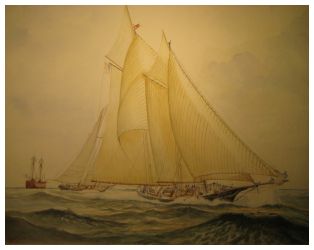

The second race for the America challenge was sailed yesterday. It resulted in another brilliant victory for the Madeleine.  The American yacht having thus won two races out of three, the cup remains for another season, at least, in our hand. There was a steady, wholesail breeze, with smooth water, the condition being about the same as Friday, except that the contest was over the outside course. While the match has, of course, been no test of the Canadian yacht’s sea-going qualities in a heavy wind and sea, yet it must be admitted that she has shown herself no match for our representative boat in ordinary yachting weather. As she will probably accompany the New York Yacht Club squadron on the cruise to the eastward, she will meet a scupper breeze and rolling sea, which will afford a more satisfactory test of her speed. Though fairly beaten, she has proved an antagonist by no means to be despised.

The American yacht having thus won two races out of three, the cup remains for another season, at least, in our hand. There was a steady, wholesail breeze, with smooth water, the condition being about the same as Friday, except that the contest was over the outside course. While the match has, of course, been no test of the Canadian yacht’s sea-going qualities in a heavy wind and sea, yet it must be admitted that she has shown herself no match for our representative boat in ordinary yachting weather. As she will probably accompany the New York Yacht Club squadron on the cruise to the eastward, she will meet a scupper breeze and rolling sea, which will afford a more satisfactory test of her speed. Though fairly beaten, she has proved an antagonist by no means to be despised.

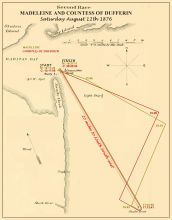

There was a thick fog in the bay as the Judges' steamer, W. E. Gladwish, steamed down to the club house, and there was a long delay before the fog cleared up sufficiently to take the contestant in tow and make for the starting point at the point of the Hook. They arrived there about 11:30 o'clock, and, after being cast off from the Gladwish, made sail and tacked to and fro, awaiting the starting signal, which was delayed awaiting a more favorable breeze. Notwithstanding the early hour, and the fact that it was an ocean race, there were several steamers clustered around the starting point, most of which accompanied the contestants. The course was twenty miles to windward from Buoy 5 at the point of the Hook. The wind was south southeast, which was the course given.

There was a thick fog in the bay as the Judges' steamer, W. E. Gladwish, steamed down to the club house, and there was a long delay before the fog cleared up sufficiently to take the contestant in tow and make for the starting point at the point of the Hook. They arrived there about 11:30 o'clock, and, after being cast off from the Gladwish, made sail and tacked to and fro, awaiting the starting signal, which was delayed awaiting a more favorable breeze. Notwithstanding the early hour, and the fact that it was an ocean race, there were several steamers clustered around the starting point, most of which accompanied the contestants. The course was twenty miles to windward from Buoy 5 at the point of the Hook. The wind was south southeast, which was the course given.

At 12:15 P.M. the starting signal was given. The Madeleine went over the line at 12:17:24, and the Countess of Dufferin at 12.17:58. As General Butler had expressed a desire to try the America against the Canadian, her time was officially taken at 12:22:09, and that of the Wanderer which also started at 12:23:41. The wind, though light at the start, gradually freshened and before an hour blew a beautiful whole-sail breeze. The Canadian warned by the blunders of Friday had enlisted the services of Joe Elsworth, "who make no mistakes." His conduct in sailing the stranger was criticized by the New York Yacht Club men on board the judge’s steamer, who denounced it as unpatriotic.

The tide was high water slack, and all ran quickly off on a leg to the eastward, on the starboard tack. For fifteen minutes the Countess out pointed the Madeleine, although the latter pursued her regular plan of reaching ahead first, and showing her Weatherly qualities afterwards. At 12:30 the Countess continued to work to windward in a way that, looking from the judges' steamer, boded the Madeleine no good. The Madeleine, however, was slipping through the water faster, and increasing her lead slightly. All were steering about south east as close hauled as they could be.

The tide was high water slack, and all ran quickly off on a leg to the eastward, on the starboard tack. For fifteen minutes the Countess out pointed the Madeleine, although the latter pursued her regular plan of reaching ahead first, and showing her Weatherly qualities afterwards. At 12:30 the Countess continued to work to windward in a way that, looking from the judges' steamer, boded the Madeleine no good. The Madeleine, however, was slipping through the water faster, and increasing her lead slightly. All were steering about south east as close hauled as they could be.

At 12:45 o’clock they were all stlll on the same tack, and fast setting away from the Judges' steamer, which remained hove to. The Madeleine now began to point better, and by 1 o'clock was eating up in the windward of the Countess at a rattling rate, as well as slipping through the water faster. At 1:10, nearly an hour after the start, the Judge's steamer got under way, ang the log was thrown over and the twenty miles steam to windward commenced. By this time the hull of the Madeleine was nearly out of sight, while those of the rest could be clearly distinguished, showing that she was a good leader, although from the changing of the steamer, the relative position to windward or leeward could not be made out. At 1:30 the steamer was up on the quarter of the contestants. The Madeleine was nearly a half mile ahead and to windward of the Countess. The majestic looking Wanderer was being badly beaten by that wonder of the seas on a wind, the America, which was to show the stranger that there was a yacht afloat, built a quarter of a century ago, that could beat a crack craft launched but yesterday.

About 2 P. M., the Judges’ steamer was abreast of Sandy Hook Lightship, showing that about seven miles of the course had been sailed. From the steamer, which was six or seven miles off, it seem that the Madeleine was over a mile to windward, and ahead of the Canadian. The America was cutting out her work finely, and exhibiting her almost unequalled powers of working to windward. She was close on the heels of the Canadian, and soon after took the lead of her, and went for the Madeleine. The length of the tack made now began to excite surprise. It had been continued for miles, although policy would have dictated shorter tacks near shore. The Madeleine, however, appeared determined not to let the Countess break tack with her. Those on board the Countess appeared to be aware of this, for they still hung trimly on mile after mile.

About 2 P. M., the Judges’ steamer was abreast of Sandy Hook Lightship, showing that about seven miles of the course had been sailed. From the steamer, which was six or seven miles off, it seem that the Madeleine was over a mile to windward, and ahead of the Canadian. The America was cutting out her work finely, and exhibiting her almost unequalled powers of working to windward. She was close on the heels of the Canadian, and soon after took the lead of her, and went for the Madeleine. The length of the tack made now began to excite surprise. It had been continued for miles, although policy would have dictated shorter tacks near shore. The Madeleine, however, appeared determined not to let the Countess break tack with her. Those on board the Countess appeared to be aware of this, for they still hung trimly on mile after mile.

At 2:30 the jibs of the Madeleine were seen very plainly, while those on the Countess were scarcely visible. At 2:45 they were all hull down from the steamer, on the same tack, and the Madeleine only showed half her sails. The Madeleine at this time must have been nearly eight miles off from the steamer, and the others nearly as much. About all that could be seen was that the Madeleine was holding her own well, and that the America was on the heels of the Canadian, if not actually leading her. At 3 it was plain that the America had taken second place, and had a position to windward of the Countess of nearly a mile. At 3:05 the log was hauled in, and it showed that 18⅞ miles had been run. This was evidently a mistake, as from the bearing from the shore it could not have been more than twelve to thirteen miles. The run was therefore continued, and the miles taken by bearings ashore.

At 3:19 the Madeleine went about on the port tack, after a long board of twelve or thirteen miles, and headed up toward the judges' boat. She was at that time over two miles to windward of the Countess, and the America led the Canadian by at least half that distance. Two or three minutes later the America went in stays, and the Countess and Wanderer followed at intervals of a few minutes. There was a superb breeze, and a very slight sea, over which the pretty Madeleine and saucy looking America, dashed in a charming manner. The tack now a long one, toward the judges' steamer, which had nearly finished logging off her twenty miles, and as the superb craft bowled merrily along, under clouds of canvas bending gracefully, the sight was beautiful. The America continued to forge ahead of the Countess, and, as though determined to outstrip her famous exploits of twenty five years ago, began to walk up on the Madeleine, probably the fastest yacht in the world of her size, with the exception of the Idler.

At 3:19 the Madeleine went about on the port tack, after a long board of twelve or thirteen miles, and headed up toward the judges' boat. She was at that time over two miles to windward of the Countess, and the America led the Canadian by at least half that distance. Two or three minutes later the America went in stays, and the Countess and Wanderer followed at intervals of a few minutes. There was a superb breeze, and a very slight sea, over which the pretty Madeleine and saucy looking America, dashed in a charming manner. The tack now a long one, toward the judges' steamer, which had nearly finished logging off her twenty miles, and as the superb craft bowled merrily along, under clouds of canvas bending gracefully, the sight was beautiful. The America continued to forge ahead of the Countess, and, as though determined to outstrip her famous exploits of twenty five years ago, began to walk up on the Madeleine, probably the fastest yacht in the world of her size, with the exception of the Idler.

At 3:18 the log was again hauled in, and it showed that 20½ miles had been rolled off. As this agreed with the bearings on shore, it was evident that a mistake in computation had previously been made, and the big barrel buoy was got ready and thrown over to make the turning point. At 4:42 the Madeleine went about on the starboard tack and dashed down toward the mark, but had another short tack to turn it to the starboard, the prescribed way. Ashbury had made things unpleasant for the club once by their leaving it choice which way to turn a mark in a match race, and this race the way was distinctly prescribed.

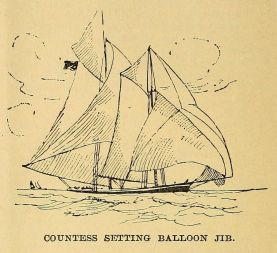

The Madeleine next went about at 4:42, and again went into stays at 4:55, with the view of weathering the buoy and speeding for home. In making this tack she essayed to set her fore-club topsail in the same expeditious style as on the occasion of the inside race, but was less successful in her attempt. The buoy was, however, turned in the same splendid style. She came up under rapid way, went round close by and ran up her balloon sails with marvelous celerity. The turn was made at 5:01:52, and the handsome yacht was speeding for home with her immense spread of canvas drawing, although the wind was not particularly brisk. It was 5:13:41 before the Countess rounded, but the America, the performance of which can hardly be omitted, went round at 5:04:53, or three minutes and one second later than the Madeleine. The Wanderer, which had been left a long distance behind, did not turn the buoy, but headed for the Hook, running abreast the Madeleine.

The Madeleine next went about at 4:42, and again went into stays at 4:55, with the view of weathering the buoy and speeding for home. In making this tack she essayed to set her fore-club topsail in the same expeditious style as on the occasion of the inside race, but was less successful in her attempt. The buoy was, however, turned in the same splendid style. She came up under rapid way, went round close by and ran up her balloon sails with marvelous celerity. The turn was made at 5:01:52, and the handsome yacht was speeding for home with her immense spread of canvas drawing, although the wind was not particularly brisk. It was 5:13:41 before the Countess rounded, but the America, the performance of which can hardly be omitted, went round at 5:04:53, or three minutes and one second later than the Madeleine. The Wanderer, which had been left a long distance behind, did not turn the buoy, but headed for the Hook, running abreast the Madeleine.

There was no special feature in the run home, except that the wind hauled to the westward to some extent. At 7:37:11 Madeleine passed between the Gladwish and No. 5 buoy, so to speak, a laurelled victor. The nautical congratulations from all the steam-boats were vociferous and prolonged, and the Madeleine answered with hearty cheers and with an abundant display of fire-works. The Countess loomed up through the darkness nearly half an hour later, passing the buoy at 8:13:58, but the America had arrived previously at 7:49.

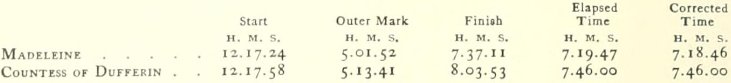

The three yachts were timed in this race as follows, the Americas time being only shown for comparison, as she was not in the race:

Madeline beats Countess 27m. 14s., and America beats Countess 19m. 9s.

The Madeleine was taken in tow by the Grant and brought down to Stapleton, where there were, of course, more congratulations. Her victory is complete and beyond cavil, the cup remains in possession of the New-York Yacht Club, and the necessity for a third race is obviated.

The Madeleine was taken in tow by the Grant and brought down to Stapleton, where there were, of course, more congratulations. Her victory is complete and beyond cavil, the cup remains in possession of the New-York Yacht Club, and the necessity for a third race is obviated.

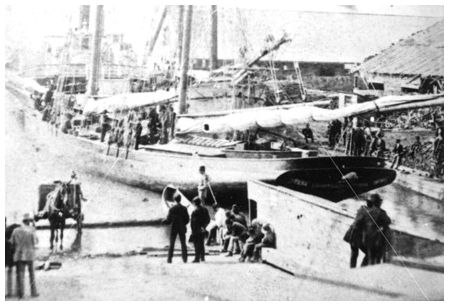

After the race the Countess of Dufferin was stripped and laid up at New York, and then the financial troubles that had beset her since she was launched began to come to a head. Captain Cuthbert, who owned the largest share in her, attached her in an effort to force Major Gifford to sell his share. Cuthbert still had faith in her and it was said to be his intention to get control of her, raise enough money to alter her with a view to making her faster, and then to challenge for the Cup again.

These plans fell through and she was finally sold at a sheriff's sale to satisfy some claims against her and eventually found her way back to Canada, later being sold to a Chicago yachtsman, who raced her on Lake Michigan.